The Naming of Cats, and an Offering

If you can read Classical Chinese, you can have a moderately good time looking in pre-20th century reference texts to see what they have for “cat.”

The late 16th-century Bencao gangmu 本草綱目 (Materia Medica) says “貓 CAT can be read as either miao or mao. They can say their own name!” The 17th-century Zhengzitong 正字通 (Comprehensive Guide to Correct Graphs) explains that cats are "of the baleful category" (陰類也). The entry in the 8th-century Wujing wenzi 五經文字 (Simplex and Compound Graphs from the Five Classics), presumably written by either a cat or a Buddhist, calls them "ferocious beasts" (猛獸), while the 11th-century Piya’s 埤雅 (Expansion to the Erya) entry for the character 貓 continues the Erya’s proud tradition of unhelpful lexicography1 with the following:

鼠害苗,而貓能捕鼠,去苗之害,故貓字從苗

Mice harm SPROUTS 苗 miáo, and CATS 貓 māo can catch mice, eliminating the harm to the sprouts. That’s why the character for CAT has SPROUT in it.

For anybody wondering how they said pspsps in the Qing dynasty, Wang Chutong’s 王初桐 1798 Mao sheng 貓乘 (A Cavalcade of Cats), the earliest collection of cat-related quotations and factoids I could find, has a section listing all the ways of calling a cat known to authoritative sources. Mi, variously written, is the clear consensus favorite, though the Yuan writer Bai Ting 白珽 suggests 汁汁, pronounced something like ji-ji at the time. (Wang comments that this “sounds like mice squeaking.”)

Sun Sunyi’s 孫蓀意 adorably titled Xianchan xiaolu 銜蟬小錄 (preface dated 1799, when she was just 16)2 has eight fascicles’ worth of feline-related quotations grouped under headings like “Origins,” “Nomenclature,” and “Tales of Karmic Retribution,” as well as a pretty impressive selection of what the preceding thousand years had to offer in the way of cat-related poetry. If you’re in the market for curious historical events, incidental verses, or bonkers little geomantic notes, Xianchan xiaolu has got you covered. (“The cat's origins lie not in China but India,” it explains, quoting a late-Ming test-prep book. “As the cat was not engendered by the qi of China, the tip of its nose is almost invariably cold, the sole exception being the day of the summer solstice.”)

Unfortunately it doesn’t have what I’m looking for, which is a list of cat names.

A while ago, Jennifer Feeley tweeted about trying to find an English name for a cat named 麻珠 “Mázhū” in a Xi Xi story she was translating. Pet names are among the few exceptions3 to the hard and fast rule that anyone who translates a personal name will not see Valhalla, but they present problems of their own.

I’ve always loved Robin Flower’s translation of “Pangur Bán,” a poem in Old Irish written in the margin of a manuscript by a bored 9th century monk:

I and Pangur Bán, my cat,

'Tis a like task we are at:

Hunting mice is his delight,

Hunting words I sit all night.Better far than praise of men

'Tis to sit with book and pen;

Pangur bears me no ill-will,

He too plies his simple skill.'Tis a merry task to see

At our tasks how glad are we,

When at home we sit and find

Entertainment to our mind.Oftentimes a mouse will stray

In the hero Pangur's way;

Oftentimes my keen thought set

Takes a meaning in its net.'Gainst the wall he sets his eye

Full and fierce and sharp and sly;

'Gainst the wall of knowledge I

All my little wisdom try.When a mouse darts from its den,

O, how glad is Pangur then!

O, what gladness do I prove

When I solve the doubts I love!So in peace our task we ply,

Pangur Bán, my cat, and I;

In our arts we find our bliss,

I have mine and he has his.Practice every day has made

Pangur perfect in his trade.

I get wisdom day and night

Turning darkness into light.

For the author and his first readers, but not for us, the name “Pangur” would obviously have belonged to a cat, a problem Flower solved by adding “my cat” to the first line of his translation. He leaves Bán (“white”) untranslated. Does it matter if a reader of Flower’s English comes away knowing less than someone who reads the original? Does it matter enough to require a different translation — say, to call the cat “White Felix,” as another version does?4 I always loved the image of a lone monk in a drafty cell, smiling and shaking the cramps out of his quill hand as he watched his white cat glaring at the walls. Would I have loved it less if I didn’t know what color the cat was?

A few years ago I read that the name “Pangur” might be related to the Welsh pannwr, meaning “fuller (n.)” — a turner of wool into felt, a treader-underfoot of soft things, a biscuit-maker and player of invisible pianos. My imaginary Pangur Bán yawned, hopped onto the monk’s bed, and set about kneading the blankets contentedly, purring up a storm. Suddenly I had a whole new thing to love.

And, even better, a few new problems for any would-be translator: Was “Pangur” actually connected to pannwr? Would the monk who wrote the poem have known that? Would he have felt it?

Would I have loved a poem that began “Me and Biscuits, my white cat?”

The Xiang mao jing 相貓經 (Guide to Cat Physiognomy), quoted extensively in Huang Han’s 1852 Mao yuan 貓苑 (A Garden of Cats), lists ways of describing the physical appearance of cats. A cat with a pure-colored coat of any color was “Good All Year Round” (四時好). “Dark Clouds Over Snow” (烏雲蓋雪) was a black cat with white fur on its belly and paws — but if only the paws were white, it was “Walking Through Snow in Search of Plums” (踏雪尋梅). A white cat with ginger spots was an “Embroidered Tiger” (繡虎); a ginger cat with a white tummy was a “Golden Quilt on a Silver Bed” (金被銀床); a calico cat, somewhat confusingly, was a “Tortie” 玳瑁猫. But these were terms used by connoisseurs to describe categories of cats, not actual cat names.

The Song-dynasty poet and ailurophile Lu You 陸游 names three cats in his poems — “Pink-nose” (粉鼻), “Snowball” (雪兒), and “Tigger” (小於菟, from wūtú, a literary word for “tiger” borrowed from the extinct Chu language). Chapter 59 of the late-Ming masterpiece Jin Ping Mei 金瓶梅 features an unforgettable appearance from a long-haired white cat with a patch of black fur called “Coals in the Snow” (雪裡送炭), a name that could also be fairly translated as something like “A Friend in Need.” But a quick browse through the literature doesn’t turn up much in the way of named cats, and I’m looking for something a little less transparent than “Pink-nose” or “Snowball.”

What I’m looking for, Wubai 五白, is stupid easy: “Five White,” two characters you learn in the first week of Chinese 101. This was the name of the Song poet Mei Yaochen’s 梅堯臣 cat, whom I picture having dark fur with white paws and a white patch on its forehead or tail. I’ve got no evidence for this; it’s just a guess.5

As with “Mazhu” and “Pangur Bán,” the name poses a problem for the translator, and none of the solutions I can think of are all that great. “Five White” is awfully clunky. “Wubai” is meaningless and (considering that Mei lived much too early to speak Modern Standard Mandarin) not even accurate. There are common pet names that do in English what I think 五白 is doing in Chinese, but they would feel as distractingly out of place in the poem I’m about to translate as “Biscuits” would in the context of 9th century Irish monasticism.

The best solution I can think of is the one I’ve gone with: prefacing the poem with a long digression about names and descriptions in the hope that by now you will be picturing a cat, maybe one you knew once. Think Boots; think Socks. Read “Five White” or “Wubai” and imagine, long ago, someone’s Mittens.

梅堯臣 - 祭貓

自有五白貓,鼠不侵我書

今朝五白死,祭與飯與魚

送之於中河,呪爾非爾疏

昔爾嚙一鼠,銜鳴遶庭除

欲使眾鼠驚,意將清我廬

一從登舟來,舟中同屋居

糗糧雖其薄,免食漏竊餘

此實爾有勤,有勤勝雞豬

世人重驅駕,謂不如馬驢

已矣莫復論,為爾聊郗歔。

Mei Yaochen - An Offering

My cat Five White. After I got you,

The mice stopped nibbling at my books.

This morning, Five White, you died.

I made offerings of rice and fish,

Left them with you in the middle of the river,

Chanted prayers — to send you off, not to send you away.

I remember how you caught a mouse

And ran around the yard with it, crowing,

To put a fright into the other mice

And clear them out of my little home.

From the day we came aboard this boat,

We shared a room and meager board.

Dry rations, and little enough of them —

It would have been rat turds and scraps

If it wasn't for you. You did your job

and worked harder than any chicken or pig.

People care only for beasts of burden,

Praise only the donkey and the horse —

Well, let them. I've no heart to argue.

I'll be weeping for you a while yet.

I’m not being fair to the 3rd c. BCE dudes who wrote the Erya, which is not really a dictionary so much as a collection of factoids about characters. Sometimes those factoids include definitions; sometimes, as here, they’re punny little mnemonics about characters’ pronunciation or structure.

For a sense of how useful this generally is to the working sinologist, imagine looking up “money” and finding “mo’ money mo’ honey” — except you also have to guess at the pronunciations of “mo’,” “money,” and “honey,” because characters.

Literally, “Notes on Cicada-Nommers.” “Cicada-nommer” (銜蟬 xianchan) was a conventional word for cats at least as far back as the Song — I first encountered it in an incidental verse by Huang Tingjian 黃庭堅 (1045-1105) called “Cat Wanted” (乞貓):

秋來鼠輩欺貓死,

窺甕翻盤攪夜眠

聞道狸奴將數子,

買魚穿柳聘銜蟬Since last fall, the mice have taken advantage of my cat’s death —

poking their heads into jars, upending plates, and ruining my sleep.

I heard your cat had a litter of kittens,

So I bought a fish and put it on a stick to engage a cicada-nommer.

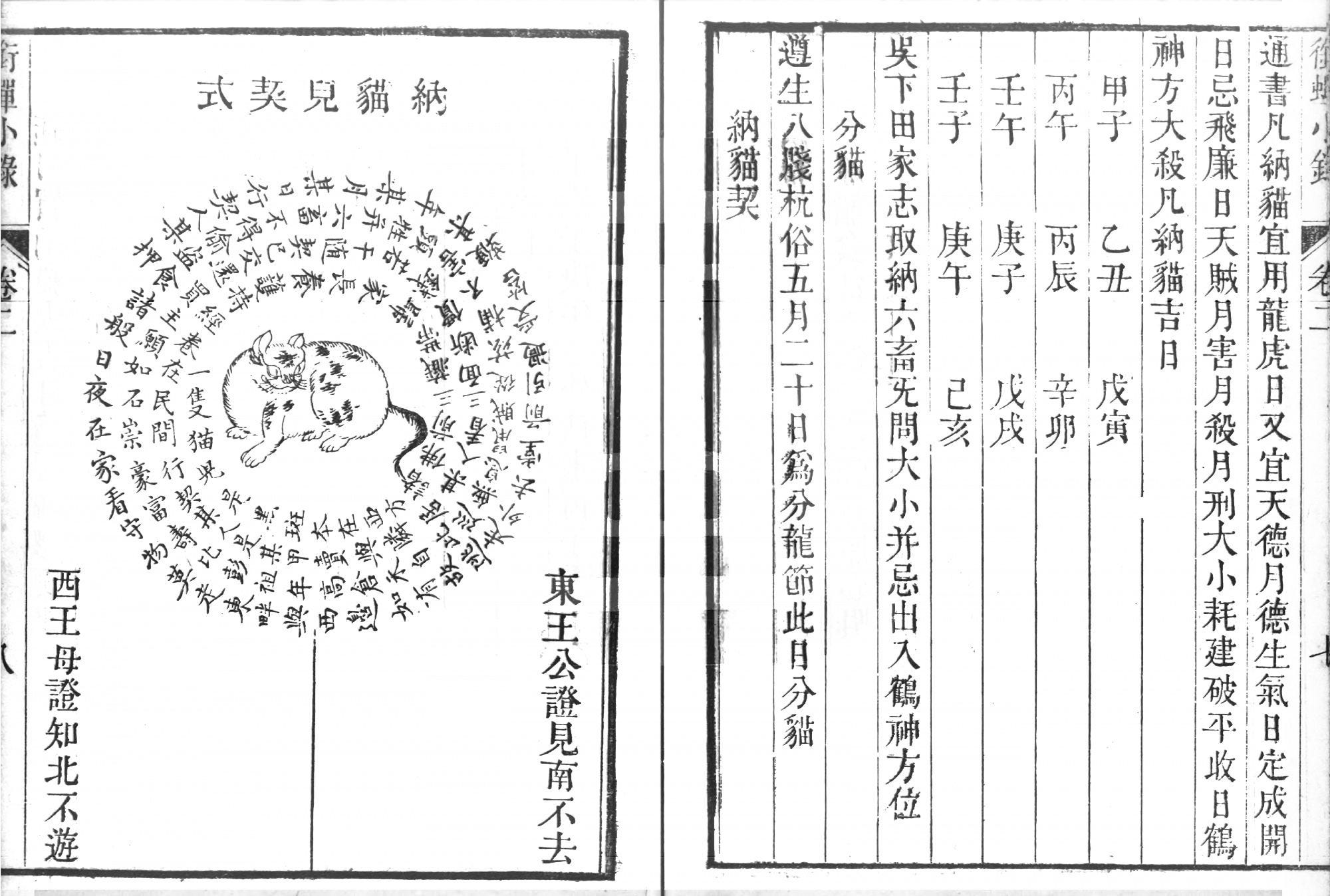

The verb I’m translating as “engage” here, 聘 pin, mostly shows up in the sense of 招聘 zhaopin / “to recruit” in modern Mandarin, but it was also the verb used for arranging the marriage of a primary wife. This is probably just a coincidental quirk of usage — but the earliest surviving guide to cat ownership, Yu Zongben’s 俞宗本 late 14th-c. Namao jing 納貓經, describes settling a new cat in one’s home in much the same way one would a new wife.

Off the top of my head, the exceptions are pet names, nicknames, pen names, screen names, and anything else intended primarily to be meaningful — the key words being “intended” and “primarily.” You never translate a government name: Yes, Chinese names are written with characters; yes, those characters are chosen for meaning as well as sound — but nobody walks down the street thinking “oh man, just wait til Nationbuilding Chen finds out Earthquake Zhang slashed his tires.” Translating personal names tends to be done more often to female characters than to male ones, and the effect ranges from “gross Orientalism” to, at best, “tacky chinoiserie.”

An example of Doing It Right is David Hawkes’ handling of peripheral character names in The Story of the Stone, his translation of 紅樓夢 Honglou meng: the Jia family names their household servants like pets, and Hawkes translates accordingly. He also goes Latinate for the religious names of monks and nuns, and French for the professional names of performers. It’s an ingenious, incredibly well-executed way of restoring some of the information passively available to a reader of Chinese. Unfortunately, it’s probably not applicable in most contemporary contexts.

There are other versions of “Pangur Bán” in English, but you can safely skip all of them, even Seamus Heaney’s. The version by Paul Muldoon in The Penguin Book of Irish Poetry is as smarmily punchable as every other attempt at a poem that sub-McGonagall talent-vacuum has ever committed.

Paul Rouzer renders 五白貓 as “calico cat” in his translation of a poem by the Tang-dynasty Buddhist poet Shide (拾得 17), but it’s not clear to me where he’s getting that from. (I’m sure he has his reasons — I just don’t know what they are.) In any event, the second line of the Mei Yaochen poem makes it clear that 五白 is a name here, not a description.

“...to send you off, not to send you away...” - when a phrase is right, it's right. And often it seems like being right is poetry enough. This whole post is most felicitous.

Re 五白, why not take the middle way (or unwobbling pivot, whatever) between transliteration and translation, and call it "Wu-itey"? Oh...because that's the worst idea you ever heard? Ah. Nevertheless,